The Hindostan whetstone – sometimes called the Hindostan Oilstone or Orange Stone – were mined from southern Indiana during the 19th and 20th century. The mine was located in Northwestern Orange Country, Indiana and were exported during their time of production through North, Central, and South Americas as well as Europe and Asia. This variety of stone is a form of heavily compressed siltstone known as tidal rhythmites. Due to its unique formation, distinctive lines or banding are commonly found on the side (or in rare circumstances the top) from where the different layers of silt were deposited.

Sections

Hindostan Whetstone Use and Performance

Hindostan Whetstone Varieties

History and Formation of the Hindostan Whetstone

Hindostan Whetstone Use and Performance

Hindostan whetstones were most commonly referred to as a type of oilstone but can be easily used with water while providing equally good results. These are fine-grained siltstones which contain small grains of silica/quartz in uniform size and quantity throughout the whetstones composition. The stones are generally very fast cutting even with finer varieties, especially when a slurry is generated from the base stone before blade work is performed.

Hindostan whetstones are prone to “pore-clogging” as the slurry is worked into a mud-like paste. To keep a Hindostan whetstone performing as a fast-cutting stone when using water, slurry should always be kept thin (avoid the development of thick mud) and the surface should be frequently re-conditioned with a slurry stone or diamond plate to expose new abrasive material. Hindostan whetstones are very compact and wear slowly in general, even when refreshed frequently, ensuring the stone will last a very long time with prolonged use.

The stone can alternatively be used with oil instead of water to achieve a working surface that requires less frequent refreshing. Hindostan whetstones of all varieties are very porous stones though and will readily suck up oil throughout the stone. Due to this, serious consideration should be given before using oil on the stone if the stone has never had oil on it before or has been fully degreased. If used as an oilstone, a little bit of oil should be added the surface of the stone after a bit of slurry has been formed and allowed to dry on the sharpening surface. This produces a very fine surface on the Hindostan stone and allows for more extended performance. In this case, the oil allows the abrasive particles on the surface to avoid getting worn down as quickly, allowing for the longer cutting life. I personally avoid using oil on Hindostan stones given how much effort it takes to degrease them and the relatively equal performance you get between water and oil. Primarily, water or oil simply changes technique of use.

Hindostan Whetstone Varieties

It is exceedingly rare to find a Hindostan stone today which is labelled, let alone labelled with the variety type left upon the stone. These stones were often sold with no label attached to them. None the less, there were quality and performance terms the Hindostan stones were sold under and can be harkened back to today:

Export Quality / Extra Quality

- The hardest and finest variety of Hindostan, typically white or yellowish white in color. These stones were sold often as razor hones, and are the variety best suited towards that end.

Washita Finish Quality

- The middle level for the Hindostan variety of whetstone and the most common type, these were most commonly grayish to creamy white in color and had a good mix of cutting power and fineness. As the name implies, their performance was comparable to a Washita whetstone.

Number One Quality or Orange Stone

- These were the lowest and coarsest grade of Hindostan whetstones, varying in color from a blueish gray to an orange or yellow variety. These stones were commonly roughly finished when being sold.

Pike Fastcut Sharpening Stone

- Usually these were not labelled as Hindostan stones, but all version of the Pike Fastcut which were natural stone were Hindostans. These stones did not use the grading variety of Extra/Washita/No. 1 but would usually be the most comparable to a Washita quality stone.

Canada Oilstone

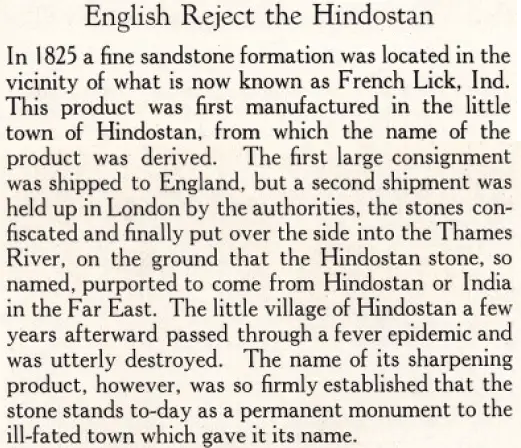

- These are Hindostan stones which were relabeled for sale in the UK in the late 1800s. This was primarily due to an issue with the name “Hindostan” and the misunderstanding that the stone was from America not India. A bit more about this is covered in the history section below. The Canada Oilstones range across the Extra/Washita/Number One quality range.

History and Formation of the Hindostan Whetstone

The Hindostan whetstone is a quarz-rich siltstone with millimeter thick horizontal layers known as laminae. These laminae layers are separated by thin clay deposits (from low-tide formations) which create the visible layering on the side of the stone. These layers were formed in sizes ranging from 8 to 20 feet in thickness and occur between Pinnick and French Lick Coal Beds of the region. These formations run from Fountain County all the way to the Ohio River (Perry and Spencer Counties). The easily accessible formations which are at the surface of the ground level are only present in Orange County, Indiana.

The Hindostan whetstone is a tidal rhythmite, this means the whetstone layers (laminae) thickness was created by the daily or semi-daily levels of ancient high and low tide sediment build up during the Pennsylvanian period 300 million years ago. These high and low tides created thick and thin layers within the stone laminae which are referred to alternating couplets. Due to the shift in tides on a daily basis, each of these alternating couplets represents a single day during the Pennsylvanian Period. These patterns are so telling in fact that they can be used to calculate precise rates of sedimentation and the lunar cycle of the period of stone creation. At the Dishman Quarry it took only one year to form a 10-foot-tall bed of Hindostan stone through this process.

The ground level stone in Orange County, Indiana was commented on by David Dale Owen in 1838 who inspected the stone and described it as “remarkably fine grained, white, and uniform.” The stone contains many different work-shaped trace fossils throughout which were also commented on. His brother Richard Owen visited several quarries in the area to study the well-preserved fern and lycopod tree fossils within the stone beds. In 1875, Edward T. Cox described the Hindostan whetstone as superior to other known gritstones and as containing magnificent, fossilized flora.

The Hindostan whetstone was sold under both the Hindostan, Orange Stone, Pike/Norton Fastcut, and Canada Oilstone monikers.

From Pike’s Sharpening Stones and Development (1915) on the rejection of Hindostan stones from the English, resulting in the creation of the re-labeled Canada Oilstone variety: